In Process: John Harvey on The Return

'Just like the journey of repatriation, the writing process collapses time. You invite the stories in. You write your way out.'

By John Harvey

Posted May 09, 2022

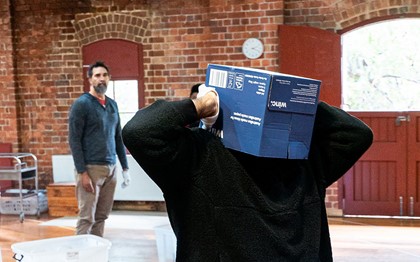

John Harvey reflects on his process writing The Return.

The Return is an epic, true story, that unearths a dark history of human remains trafficking in Australia. It’s a reminder that that time is not linear and buried history not only rises, but we walk with it side by side today.

I was first approached in 2017 to write The Return. I had written my first play Heart is a Wasteland, presented at The Malthouse earlier that year. It was a two hander—a character driven piece—of two lovers meeting in the middle of the outback and diving headfirst into a whisky-fuelled affair.

The Return was a completely different proposition for me as a writer. I had heard of stories from my own community of Saibai Island in the Torres Strait and had watched news stories about repatriation. I had seen artefacts displayed in ‘trophy’ cabinets in museums in this country and across the globe.

The idea of a play on repatriation of Ancestral remains had come from co-director Jason Tamiru. I had known Jason for a number of years, first meeting him when he worked at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival. But until writing The Return what I hadn’t known was that he had worked on the repatriation of Ancestral remains. As I began the journey, I met with Jason many times and had lengthy conversations with him about his experiences. I learnt that they were extraordinary and multifaceted. I couldn’t imagine the weight he must have carried on his shoulders: the cultural obligation and the disturbed energy he must have felt working with Ancestors, communities, and institutions.

Jason took a few of the creative team on a trip to Country with some of his family to learn more of this story. It was a deep and profoundly moving experience, mixed with sadness for the loss, anger for the injustice, healing for the wounded heart and surprisingly, some incredibly gut-busting irreverent and hilarious moments. I’ve carried this experience through the writing of the play.

We met with people from Melbourne Museum, The University of Melbourne, and the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council, who work in repatriation now. I carried them with me too, and the incredible, difficult work they do.

I read papers, articles, and watched documentaries. They began to unearth a scale of stolen Ancestral remains that was beyond my imagination. The material consisted of unthinkable brutality, a darkness of humanity, and disturbingly a laissez-faire practice of stealing and trading Indigenous Ancestral remains. This was a time where ‘shooting season’ was a term being used openly between institutions in relation to collecting ‘fresh specimens’—a highly valuable commodity. And it was all done in the name of science. A science based one man’s theory of evolution that conveniently had the white man at the evolved end of the scale, with the mainland Aboriginal at the other end.

In reading the research material I would enter a reality that was controlled by white men, who spoke freely of the brutality they inflicted on the ‘blacks’, while other white educated men boasted about their scientific breakthroughs and how to anatomise a fresh specimen in the field. It was often too much and I would find myself standing away from my desk, walking out of my office and taking a long walk along the Maribyrnong River. The voice of ‘history’ shackled me, but if I sat still within myself, the voice of the voiceless would guide me.

Typically, my writing routine would involve writing in the early hours of the morning at home, before the sound of little feet would come pattering down the hallway. However, with the nature of the research material I had buried myself in and the writings I had begun to explore, I realised I couldn’t take this material into my home anymore.

There have been many iterations of this play. We originally focussed around Jason’s story but it didn’t feel right for him; after all, this isn’t one person’s story, it belongs to many, with thousands and thousands of Ancestral remains being traded. That resonated with me, but I struggled to find the new path. I started with writings that were simply responses to the research material I was reading, a cathartic process for me to deal with the material and to explore a creative energy and spirit to tell this story. These writings weren’t for anyone else but myself.

Then I began to write scenes—not knowing where they would go—but just trying to put something on the page. I tried not to overthink it. I tried to leave the unbearable weight of responsibility I felt in a bag, shoved to the corner of the room. And then I would write another scene. The scenes weren’t necessarily connected to each other, but were more a reflection or theatrical responses to the material.

I spoke at one time that this play might be a series of vignettes, that would traverse characters and time. I didn’t really know where I was going. I was writing because I had to, because I needed to, because I said I would.

As a writer, I had accumulated these stories from the distant past, the near past, and the present and they were not just interwoven, but bound in a truth that sat beyond a linear understanding of history. The work that Jason had done and those working in repatriation today co-exists with the stories of anatomists and grave robbers of a brutal colonial past. All of these things live side by side.

I thought a lot about time in the context of history. It’s only time that makes things historical. But for Indigenous people, perhaps for all of humanity, time is not linear and it only exists in the physical world. This sparked a spiritual and creative connection for me and I went from writing one person’s story, to many peoples, and then finally to the story that I was always meant to write. Just like the journey of repatriation, the writing process collapses time. You invite the stories in. You write your way out.

The Return is a call for us to come back to our humanity and to find a belonging to each other. There is not one story of repatriation—and there are many beings in this world and beyond who are working towards it.

John Harvey is an award-winning writer, director, and producer for theatre, film, and television of Saibai Island (Torres Strait) and English descent. He is the creative director of Brown Cabs.