Provocation: The Theatre of The Internet

'The internet may not be the theatre’s opposite, but in the past nine months these two forces have slid increasingly into one another’s orbit in ways we cannot ignore. '

Posted Dec 17, 2020

Marcus Ian McKenzie unpacks the dramaturgical possibilities of the digital space, and theatre’s vexed relationship with the internet.

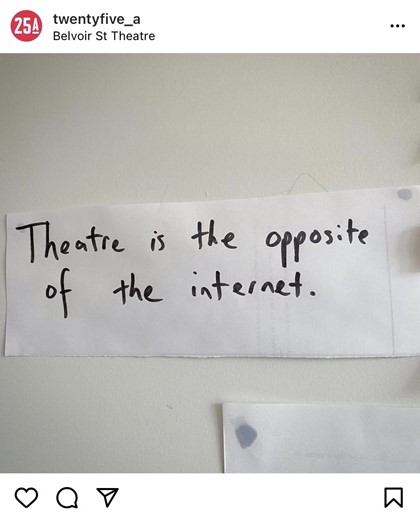

A couple of weeks ago a curious post appeared on the Belvoir 25a Instagram account. Like an oblique monolith discovered in the middle of the desert unaccompanied by any contextual statement, the post displayed a photograph of a handwritten note stuck to a door:

Beneath it, a string of approving comments and emojis that suggested this small phrase had perfectly articulated the collective unconscious of a live performance community greatly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The author of this aphorism remains, in true internet fashion, unknown.

For me the post had a number of possible meanings:

-

That patrons of live theatre should abandon the stagnant confines of their breakout rooms and return once more to the domains of the real;

-

that the former will never be a substitute for the latter;

-

that the former offers salvation from the latter.

The implication that the theatre offers things that the internet does not seems fair enough at first. But are the theatre and the internet truly so diametrically opposed? Is the theatre really an antidote for the cold, virtual annals of cyberspace that have so rapidly taken centre stage in our lives during the COVID-19 pandemic? Can it offer a vaccine for our smartphone addictions, scrolling fatigue and webinar lethargy? And can these domains coexist, or are they oil and water?

Let us interrogate for a moment this supposed distinction between the theatre and the internet.

As we plunge headfirst into this weird new decade of 5G and deep learning neural networks, it feels increasingly futile to delineate boundaries between the internet and everyday reality. With every facet of our lives hurtling ever further into the online psychosphere, the internet itself is, as Hito Steyerl puts it, ‘moving offline’1. The mythologies, languages and symbols of the internet increasingly infiltrate and inform culture from all sides. Elon Musk and Grimes give birth to an avatar. Your meme dealer sits next to your Adderall dealer on speed dial. You create a deepfake of yourself to attend university lectures on your behalf.

Works like Halory Goerger and Antoine Defoort’s Germinal chart the genesis of the internet with the same reverence as the genesis of sentient life on earth. It may only be a matter of decades before the words 'online' and 'offline' hold no relevance to modern life, and as the border between virtual and actual spaces continually blurs, there is no reason to think theatres will remain immune. What is the difference between watching a performance from a one hundred seat auditorium and from the comfort of your living room when all your audiovisual sensory data is filtered through the same series of bionically implanted data-sorting algorithms beneath the surface of your skin?

But the future is not yet here, so perhaps the distinction is still pertinent. In 2020, theatres across the world went dark and put their ghost lights on, leaving theatre-makers, choreographers, performance artists and their ilk few options but to navigate the uncharted oceans of the internet. Whilst many innovative online works in the past nine months have felt like attempts to critique the boat whilst building the boat whilst plugging holes in the already sinking, partially-constructed boat—one thing has united the majority of contemporary performance sojourns in 2020: they have taken place online.

In the realm of datamoshing video, lagging audio, physical disembodiment and scattered attention spans, can screen-based performance—whether prerecorded, streamed in real time or a combination of both—be considered legitimate? And what, fundamentally, differentiates it from cinematic forms like Netflix and Youtube?

These questions get to the heart of what exactly 'performance' (and in turn, theatre,) is. Jonah Westerman invokes Marcel Duchamp’s notion of the 'inframince' to define performance as a threshold that joins form to experience:

This infinitesimal, vibrating, uncertain distance is what Duchamp called the ‘inframince’... too thin to be thin, or even more thin than thin. His examples include the warmth felt on the seat of a chair just after someone gets up from it and the space between the front and back sides of a sheet of paper. We experience the infrathin when ‘tobacco smoke exhaled also smells of the mouth which exhales it’, or when we view an image painted on glass from the non-painted side. The two elements—smoke and breath, or glass and paint—remain intelligible, perceptible, but where one stops and the other starts is unidentifiable, too fine to grasp. That kissing spatial plane, that temporal membrane, is performance as a medium.2

The endless infrathin membranes of the internet provide not only valid sites for the establishment of such thresholds, but in 2020, exceptional ones. In the age of Twitter and hyperindividualism, everyone is a performance artist.

Social media continues to emerge as a performative arena in which fantasies of the self are created, dismantled and recreated over and over again. Here, identities slide and meld with the simple flick of a finger.

These channels of self-expression have been captured by megacorporations like Google and Facebook, and fed back as the lifeblood to the masses to the point that the very validity of artistic practice is called into question. Filmmaker Adam Curtis warns:

We may look back at self-expression as the terrible deadening conformity of our time. It doesn’t mean it’s bad and it doesn’t mean it’s a fake thing. It’s gotten so that everyone does it—so what’s the point? Everyone expresses themselves every day.3

We must question whether the forms of expression offered by the theatre are any different (or better) than those perpetuated by social media. And, concurrently, whether there is any disruptive potential to be gleaned within the endless deluge of online imagery.

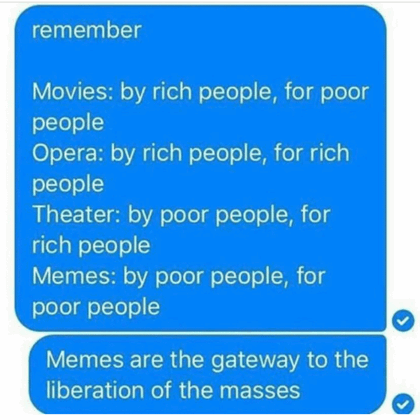

Erupting out of this situation, the radical potential promised by cybernetic heralds of the 80s and 90s may perhaps be found in internet-specific forms like meme culture. With its inherent intertextuality, infinite permutations of self-referentiality, all entwined within a double helix of permanence and disposability, memes exist at the cutting edge of performance. Memes are micro happenings within the house of mirrors of the internet—They bow to no institutional rule and cross-pollinate ideologies with often bewildering furore.

Memes may not necessarily be for everybody, but they are for anybody.

With 4.66 billion users in 2020, the internet has the potential to be a great leveller—it holds the promise of destroying old hierarchies and power structures as much as it does of reinforcing them. Nowhere is the emancipatory potential of memes captured more succinctly than in memes themselves:

Let us return to this idea of the theatre as a kind of respite from the cultural sinkhole of the internet. Theatre’s survival from its ancient roots into modernity is no lucky scrape. What entices people back to the theatre is its unique relationality—that ineffable exchange that happens between people within the intensified context of a live event, always teetering on the edge of brilliant catastrophe.

While all art forms may contain relational qualities, it is possible that for theatre this relationality is the primary locus of the art itself, even more so than its images, ideas, bells and whistles. In this sense, performance is a continual repetition of eternal human rituals of being together. On the internet, spectators survey the theatrical situation at arm's length, severed from the subtle permutations of energy between viewers and performers in IRL theatres. Unlike the theatre auditorium, where public affect is mined and disseminated through the divine alchemy of held breath, dimmed lighting and that ineffable stuff we call the 'presence' of the performer—live streamed performance can be a solitary, lonesome affair.

So does the removal of this congregational (the crossover here with religious ecstasy is not to be ignored) element make the isolated nature of internet-performance inherently antitheatrical?

Even with the invitation to turn on your webcam on platforms like Zoom, a spectator always has the option of leaving it turned off; of stepping back into the shadows of online anonymity. If the fundamental trait of theatre’s ontology is, as Peggy Phelan suggests, that it 'continually marks the perpetual disappearance of its own enactment'4 , then surely the true performative gesture here lies more in the hands of the audience than it does in ever-archived digital content that audience consumes?

The internet forgets nothing: it is a palimpsest upon which performances are inscribed ad infinitum. Even if you delete your art-data from the cloud, privately funded data scraping operations are actively working to harvest its remains and sell them back to the corporations you are trying to evade. It is much easier to die in the theatre than it is to die on Facebook.

Despite this agency to appear and vanish at will, is the live stream spectator rendered passive in her geographical dislocation from the performance ground zero?

In The Emancipated Spectator, Jacques Ranciere argues against a binary of passive and active forms of spectatorship, instead claiming that all forms of spectatorship are necessarily active5. While some works require spectators to interact more than others, all art is fundamentally interactive—on some level, art always requires you to participate. As Pablo Helguera states in Education for Socially Engaged Art, 'arguably, all art is participatory because it requires the presence of a spectator; the basic act of being there in front of an artwork is a form of participation'6. We can further argue that all artistic engagement requires some kind of embodied thought, and the extent to which that embodied thought occurs depends on the agency/ability of each spectator to engage and be changed.

A key characteristic that places theatre in opposition to the internet is its strong relationship to place. Theatre happens in specific places that are designed in one way or another for congregation. Even site-specific performances that occur outside of traditional locations consider very carefully their audiences’ spatial relationship to that site.

This communal dimension extends beyond the auditorium itself and into the foyer, where discussion of a performance exists as a pretext for social revelry, and vice versa. The phenomenon of 'virtual foyers' (whether on the Melbourne Fringe’s bespoke digital chatrooms, or APAM’s immersive VR club spaces for Liveworks) provide interesting forms of communication in their own rights, but undoubtedly lack the social lubrication a well designed theatre bar can offer.

While it is very difficult to imagine live performance without a site for it to occur in, 2020 has nonetheless asked us to reconsider what a 'site' might be when we no longer have the same access to conventional performance sites, or indeed public space at all. In Pleasuredome for Griffin Theatre, Harriet Gillies and Xanthe Dobbie explored the possibilities of the computer desktop as a performance space. This desktop dramaturgy is less concerned with the performance of human actors than it is with the choreography of non-human objects across a two-dimensional plane. Similarly to the machinic installations of Heiner Goebbles’ Stifters Dinge or Urs Fischer’s Play, Pleasuredome challenges traditional theatre convention by establishing a 'performance without performers', where the artists remain largely unseen yet performativity perseveres as a form of semi-automated cyber-puppetry. But rather than robotic swivel chairs or elaborate assemblages, this work incorporates what we might call a 'semiotics of screenshare': pop-up windows, GIFs, predictive text and Chrome tabs.

In The Crying Room for Arts Centre Melbourne, I created a performance for Zoom which slid between makeshift handheld video and desktop screen sharing—here, the 'site' of the performance is continually destabilised, and the 'liveness' of the event repeatedly called into question. In Pleasuredome, the audience doesn’t just switch between platforms, but consumes multiple streams simultaneously—at one point via both Youtube and OnlyFans. This specific division of attention is not merely an aesthetic preoccupation within this type of work, but an inherent part of it. Beyond the built-in fragmented visual dramaturgy of the work itself, audiences have the freedom to browse social media, talk to other members of the audience in a chatbox, read the news in a separate tab (or separate screen)—all while grabbing a piece of toast from the kitchen.

The very nature of watching a live streamed performance from the comfort of your home offers the same anonymity as watching a movie does, and watching it within a web browser further offers the temptation of what Linda Stone calls 'continuous partial attention' (CPA).

Unlike multitasking, in which our attention is divided in a balanced way for the sake of increased productivity or efficiency, CPA... 'describes a state in which attention is on a priority or primary task, while, at the same time, scanning for other people, activities, or opportunities, and replacing the primary task with something that seems, in this next moment, more important.7' For better or worse, these digressions of attention simply are not tolerated in most theatre spaces—the performance belongs not to the spectator but to the performers.

Perhaps herein lies the true dividing line between theatre and the internet. The theatre, especially in its proscenium arch format, asks us to hone our attention on one place for a set duration. Lighting, architecture and acoustic design funnel our engagement to the singular point of the stage. The most powerful soliloquies pull us into their orbit such that only our own flights of imagination may pull us free. IRL theatre demands 'presence' not only from its performers, but from its audience. Couple this with the general faux pas of using your smartphone during a show and it is clear to see how, when it comes to attention, theatre is indeed at the opposite end of the continuum to the internet, where it is practically impossible not to tumble down the rabbit hole of hyperlinks and suggested media and into the relentless crush of content collapse.

The internet may not be the theatre’s opposite, but in the past nine months these two forces have slid increasingly into one another’s orbit in ways we cannot ignore.

As we move into a post-COVID-19 epoch, artists of the theatre must not fall into the same reactionary Ludditism of the industrial revolution that saw workers burning sewing machines in the streets. We should also strive to continue to define what makes these mediums powerful in their own rights. Theatre artists must consider what the internet has to teach us, and what we, in turn, can teach it.

Marcus Ian McKenzie is an artist and performer working on unceded Aboriginal land in Melbourne, Australia. Moving between solitary experimentation and interdisciplinary collaboration, his work integrates sound composition, acting, meme-adjacent media and bad dancing. His most recent work The Crying Room premiered at Melbourne Fringe 2020, receiving awards for Best Experimental Work, Best Adaptation to Screen, and the Art Unbound Award.

marcusianmckenzie.com

- Hito Steyerl, 'Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?', e-flux, 2013.

- Jonah Westerman, 'Between Action and Image: Performance as ‘Inframedium'', Tate Research Feature, 2015.

- Adam Curtis, 'Adam Curtis on the dangers of self-expression', The Creative Independent, 2017.

- Peggy Phelan, 'Theatre And Its Mother' in Unmarked, The Politics of Performance, Routledge, London (1993), pg.115.

- Jacques Ranciere, The Emancipated Spectator, Verso, London, 2009.

- Pablo Helguera, Education For Socially Engaged Art, Jorge Pinto Books, New York, 2011 (pg. 14).

- Linda Stone, 'Beyond Simple Multi-Tasking: Continuous Partial Attention', 2009.